Out With Nipple Yeast

Advances in medical knowledge are a cause for both celebration and chagrin. Case in point is the growing scientific consensus that yeast is not a common cause of nipple pain during lactation. Also called thrush, many respectedbreastfeeding websites and books are still filled with advice on how to combat Candida albicans (yeast) nipple infections. And it takes awhile for new advances to trickle throughout clinical practice, so lots of people are still being inappropriately diagnosed and treated for yeast infection.

It’s painful to recognize that any breastfeeding advice I gave in the past was wrong. Still, better to face the facts and keep up to date than to stick my head under the sand and ignore new science. This is one I’ve known for awhile but I think the old thinking is prevelant enough to warrant more attention.

Respite

The pauses in labor can be hard to appreciate. After all the waiting for labor to start, the months of anticipation, the anxious texts from loved ones, it’s finally happening, and then… it’s not.

The art of midwifery is knowing - or guessing - when to resist the troughs of a long labor with the tools in our midwife bag (herbs, breast pump, dance music, lunges, stairs - and yes, pitocin) and knowing when to surrender. To turn off the lights and draw the curtains, arrange the pillow fortress, and allow the body to float among the lapping waves of contractions, languid as they may be.

Ana’s Birth Story

Around 5pm, I started contracting. Around six my water broke and by eight I was ready to push. The midwives came shortly after and guided me through a beautiful, gentle birth. The three of them surrounded me, but kept so quiet that sometimes I didn’t feel their presence at all.

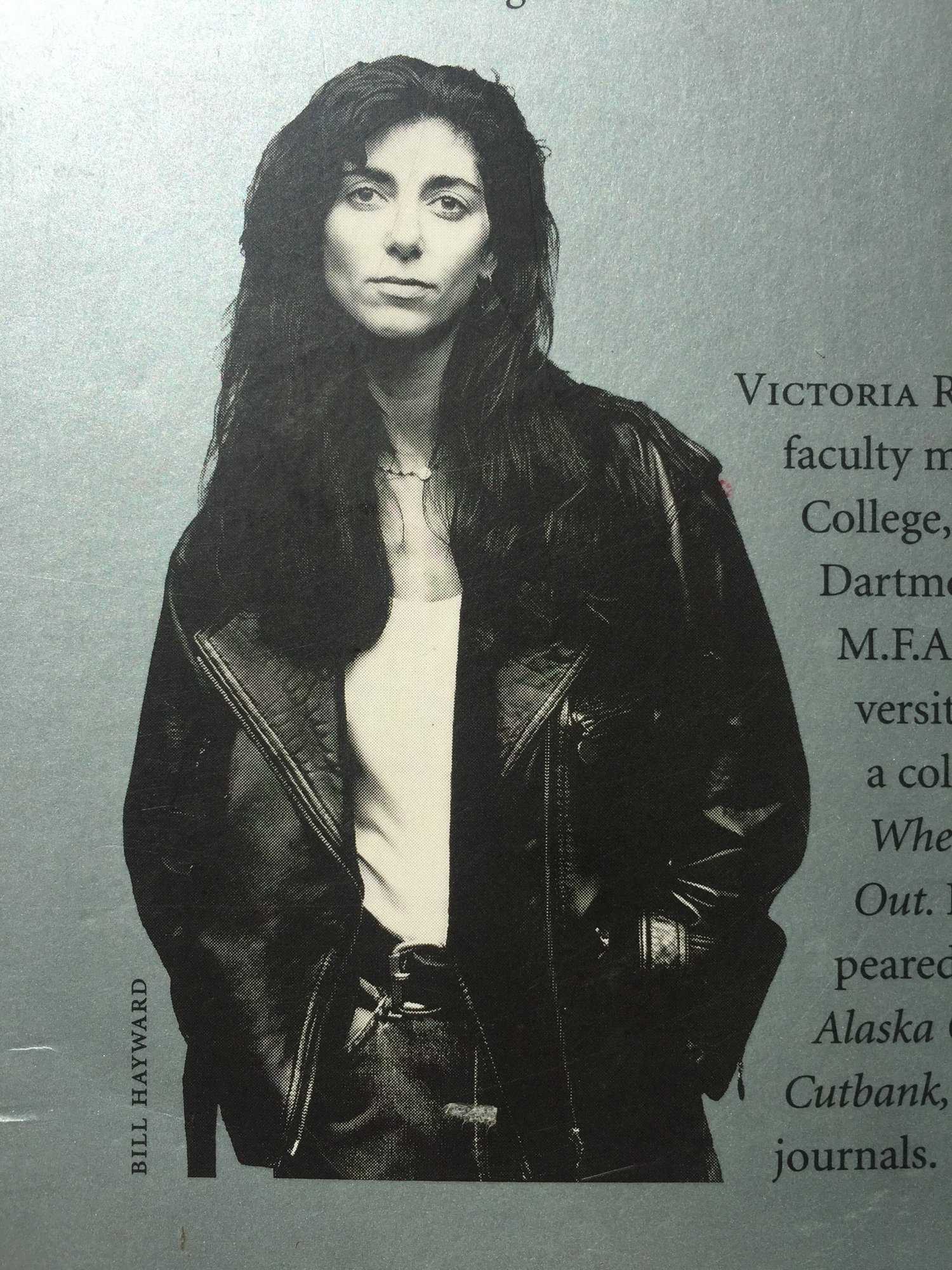

Already the World - Victoria Redel

I’ve loved Victoria Redel’s poetry since I stumbled across her first book of poems for a dollar in the basement of a Saint Paul discount book store. Look at her, coolly facing down the reader in a leather jacket on the back cover - how could I not take her home?

I bought this book in my early twenties, before the idea of becoming a midwife had implanted itself into my consciousness. How satisfying, then, to revisit these poems after years of walking with families through pregnancy, birth and the postpartum wonderment of suddenly cohabiting with an almost alien being.

Birth is like jazz - Elizabeth Alexander

Here's a birth poem by Elizabeth Alexander. I delved into her poetry after reading her beautiful memoir about the death of her husband, The Light of the World.

Neonatology

Giving birth is like jazz, something from silence,

then all of it. Long, elegant boats,

blood-boiling sunshine, human cargo,

a handmade kite —